Posted By Roger Stritmatter on January 13, 2010 – updated 5/2/2022

Don’t look now, but literary scholar and psychoanalyst Dr. Richard Waugaman has published an intriguing new chapter in the ongoing study of the de Vere Geneva Bible in Oxford University Press’s Notes and Queries.

Waugaman’s article, “The Sternhold and Whole Book of the Psalms is a Major Source for the Works of Shakespeare,” appeared in the December 2009 issue of Notes and Queries and swiftly rose to the top of the charts in the journal’s list of most read articles.

The Sternhold and Hopkins edition of the Psalms, argued Waugaman, is “a crucial but neglected repository of salient source material for the works of Shakespeare.”

A copy of these psalms is included in the Geneva Bible bound for Edward de Vere and now held by the Folger Shakespeare Library.

A year later, Waugaman followed up with “Psalm Echoes in Shakespeare’s 1 Henry VI, Richard II, and Edward III,” in which he finds that “in his history plays, allusions to the WBP serve to reinforce Shakespeare’s providential interpretation of English history.”

Both articles have been among the most read ever in the history of Notes and Queries online (Figure 1).

Taking his cue from the marked psalms of the de Vere Geneva Bible, Waugaman set out to investigate two related questions.

Sternhold and Hopkins Psalms in Shakespeare

First, how important were the Sternhold and Hopkins psalms, in a general sense, for shaping Shakespeare’s religious themes and imagery?

The received wisdom, as Waugaman explains in his first article, was “not so much.”

While scholars have recognized the generic importance of the Psalms in Shakespeare, until Waugman’s work the standard belief was that the Coverdale Psalms or those found in the Book of Common Prayer were Shakespeare’s chief Psalm sources.

Shakespeare was less familiar, it was thought, with the Sternhold and Hopkins psalms that are found with the 1570 de Vere Geneva Bible.

Not so, according to Waugaman, who documents a volley of previously undetected allusions to language unique to the Sternhold and Hopkins psalms.

“The Sternhold and Hopkins metrical translation of the Psalms is a crucial but neglected repository of salient source material for the works of Shakespeare….” concludes Waugaman.

“Richmond Noble maintained that Shakespeare quoted the Psalms more often than any other book in the Bible, and that ‘a large proportion of such quotations’ are from the Coverdale translation of the book of Common Prayer. Noble led other scholars to ignore WPB….[but I have found WPB to be a rich source of Shakespeare’s first 126 Sonnets….” (595).

De Vere Bible Psalms in Shakespeare

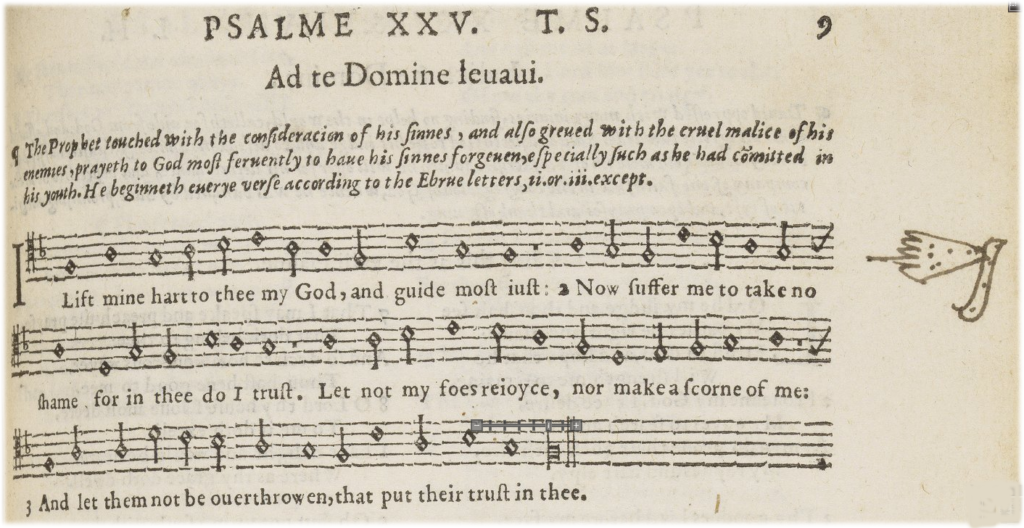

Waugaman’s second, more specific question, was whether the de Vere Bible annotations could provide a heuristic “answer key” to passages in the plays that echoed the psalms marked in de Vere’s Sternhold and Hopkins (Figure 2).

For a clickable Link, visit my portal to Luna blog entry.

He found that it could.

Turning the pages, we find that twenty-one psalms are marked in the de Vere Sternhold and Hopkins, mostly with marginal drawings of a small hand with a pointing finger.

Manicules

Manicules are pointing hands drawn in the margins of texts (Figure 3).

Manicules are a convention of active reading, centuries old by 1568, in which a pointing hand was used to mark some passage that was considered by the scribe, and eventually by the reader, worthy of attention and memory. The de Vere Geneva Bible contains seventeen of these manicules (12, 25, 30, 31, 51, 61, 65, 66, 67, 77, 103, 137, 139, 145, 146, 151 and Lamentations) marked in the body of the text, and five more (8, 11, 15, 23 and 59) in the commentary by Athanasius.

Some of Waugaman’s further findings, published thirteen years ago in Notes and Queries, are here illustrated for the first time from the de Vere Geneva Bible (Figures 4-11).

Sonnet 66 “echoes the sentiments, the imagery, and the language of Psalm 12” (Figure 4).

Sonnet 21 “is structured as a response to psalm 8” (596) “…the author of Psalm 8 is the Muse Shakespeare alludes to in Sonnet 21. . .The psalmist is an implicit prototype for the rival poet or poets of the sonnets” (Figure 5).

“’For my sin’ is a phrase that occurs only in Sonnet 83.

It occurs as well in Psalm 25:10—also its unique occurrence in that translation….It is thus one of the many instances where Shakespeare’s use of the language of the Psalms implicitly compares his words to the Fair Youth with the psalmist’s words to God…Shakespeare has been accused of a sin he does not agree he has committed…this identical phrase, ‘for my sin,’ would recall to an educated contemporary reader (including the Youth himself) the rest of psalm 25, which therefore constitutes a running subtext for Sonnet 83” (Figure 6).

“Psalm 103 has several interesting features that may have especially captured Shakespeare’s imagination….Vendler calls the diction of eight lines of Sonnet 124 ‘imitation biblical.’ It contains many allusions to Psalm 103” (Figure 7).

“In early modern England, Psalm 51 was regarded as the chief ‘Penitential psalm.’…Lady Macbeth’s words are a transparent confession of her crime, so it is fitting that they should allude to the chief psalm of confession…A close reading of this scene against Psalm 51 shows several contrasts between her actions and words, and the psalm, thus highlighting her shortcomings…”(Figure 8).

“Psalm 77 is prominently echoed in lines 897-910 of Rape of Lucrece” (Figure 9).

“Psalm 146 is also echoed in four significant words in this same stanza [of Lucrece]” (Figure 10).

“Psalm 139 (Figure 11) captures much of the theme of Rape of Lucrece, including efforts to conceal sin in the darkness of night, and its eventual revelation and punishment…The allusion to Psalm 139, as well as other allusions to the Psalms throughout the poem, suggest ‘secret thoughts’ that scholars have previously overlooked” (602).

In this blog we have seen photographic evidence that annotator of Edward de Vere’s Geneva Bible recorded a preference for seven Psalms that Shakespeare vividly remembered from a Sternhold and Hopkins edition of the metrical psalms. Professor Waugaman has explained the importance of each one in his Notes and Queries articles, giving us a guide to the significance of the manicules we can all now see.

These are not the only psalms of interest marked in the de Vere Bible, and Waugaman’s findings do not exhaust what may be said on the subject. They do, however, furnish a rather astonishing specification of the Oxfordian argument, here illustrated for the first time from the original documents of the case.

Coming in a future blog: “Psalm 137 and the Waters of Pabylon: Sir Hugh Evans cites Scripture.”

That’s not a misspelled word. In Wenglish, it’s pronounced Pabylon (Merry Wives, 3.1).

May 4, 2022 at 12:21 am

It is kind of Professor Stritmatter to marry my words with his wonderful photos of the manicules in Oxford’s Whole Book of Psalms. What he has failed to mention is his own crucial role in my discoveries. In the summer of 2008, I emailed him that I noticed wording and sentiments in Psalm 12 that are echoed in Sonnet 66. He replied that this was a new discovery, and he strongly encouraged me to keep looking for more intertextuality. We exchanged numerous emails over the next weeks. He suggested I publish my findings, without revealing that I am an Oxfordian, and without revealing that Oxford’s manicules “pointed” me to my discoveries. This was the reason I didn’t feel I could publicly thank him for his generous help in my two Notes & Queries articles.

They are available here–

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9YH_poTOlrba3VIbWowUzJvM3M/view?resourcekey=0-AOQkB4MaQItCw0BPz5Z8xA

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9YH_poTOlrbWGZPT0lPOUJrdFk/view?resourcekey=0-tEj62oMEvYN9kqFqObmdVg

May 11, 2022 at 3:13 pm

Amazing how having the “answer key” can help you with the quiz questions!

May 13, 2022 at 8:46 pm

I wonder if you have any idea why Psalm 137 was marked by that hand. Thank you in advance.

May 13, 2022 at 9:36 pm

Sounds like you may have your own theory. It does show up prominently in Shakespeare, but I have no idea what the reason for the original marking was. Only that Psalm 137, like the others, is significant in Shakespeare.

May 14, 2022 at 6:10 am

You’re right. A complete theory with several clues. But it’s way longer than to fit in this place. Hank Whittemore (my good friend) knows a lot about it. But this is your blog, not mine 🙂

May 14, 2022 at 12:56 pm

I try to avoid teleological explanations that involve mind-reading and stick with interpreting material evidence.

May 14, 2022 at 3:01 pm

I’m really lucky that Mr. Andrew Gurr found my interpreting visual clues to be “very adroit”, and expressed his wish to see my “entire production”.

But I see your point, it makes sense. It depends on the nature of material you explain.

August 11, 2023 at 7:36 am

I suspect the significance (to Oxford) of Psalm 137, is revealed by another manicule. The grand hand on the Westminster memorial points to the “cloud capt Tow’rs” that are a baseless fabric. It predicts Nothingness for the Pseud’Or captors of the Crown Tudors. Psalm 137 has been marked for alluding to a captivity that ties Judah to Tudah.

February 23, 2025 at 12:54 pm

I just discovered a further significance of the maniculed Psalm 12, thanks to Robert Alter. He translates its third verse as “Falsehood every man speaks to his fellow, smooth talk, with two hearts they speak.” Two hearts–sounds like “Corambis”! The original Hebrew is “beleb waleb,” meaning double-hearted, or hypocrtical. (The Latin Vulgate translates the phrase as “in corde et corde.)

So, a further reason Oxford pointed to this psalm with a manicule. Hebrew was taught at Cambridge when he studied there (it was Henry VIII who paid a stipend of £40 to its Hebrew professor), and he probably learned it, along with Latin and Greek. There was a surge in interest in the original language of the Old Testament during the Reformation, with Luther’s advice, “Sola scriptura.”

Psalm XII made Oxford think of Burghley, his father-in-law and former guardian, as the hypocrite who tied Oxford’s tongue. I suspect this psalm not only inspired Sonnet 66, but also the original Polonius in the First Quarto of Hamlet, Corambis the Hypocrite.